Tim Sheridan designed and built a radio-controlled (RC) servo “pup” capable of sitting, standing, walking, and barking. Alex Iles helped with the microcontroller implementation.

[]

Keeping Austin weird before weird was cool

Tim Sheridan designed and built a radio-controlled (RC) servo “pup” capable of sitting, standing, walking, and barking. Alex Iles helped with the microcontroller implementation.

[]

Bob Comer (and son, David) have been working on a surveillance robot with remote telepresence. The robot is constructed using a PVC frame and drive components (motor, gearbox, and wheels) scavenged from old kids’ electric ride-on toys.

The robot is equipped with

The robot is programmed in Dynamic C and has a web page as an interface. You can drive the robot from any computer with wireless networking and a web browser.

[Image and text originally from http://wiki.therobotgroup.org/wiki/RobertComer]

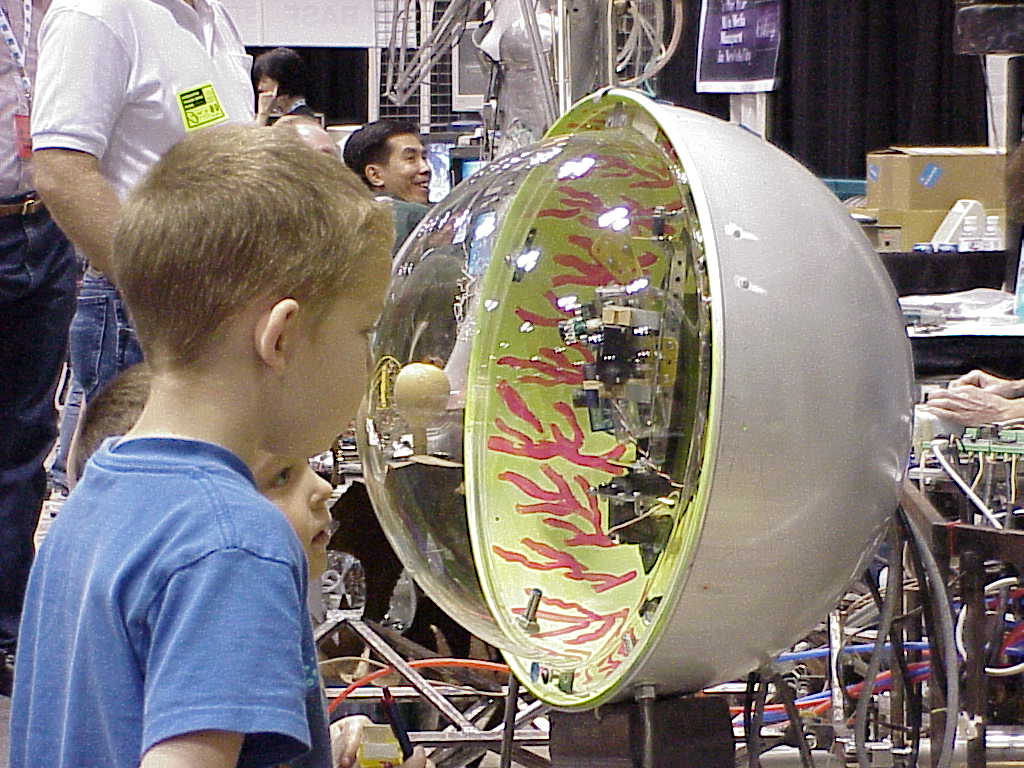

Tom Davidson & Sonia Santana are the forces behind, EyeBot, a mobile platform telepresence robot based on the Mobile Platform Mechanics. The control is a very basic R/C 4-channel using two 12V electronic speed controllers, and 2 R/C car servos.

The “Super-Rooster” speed controllers are capable of 128-levels of proportional control in forward and reverse and can handle up to 150 Amps at 12 Volts.

The servos are used in a gimbal which carries two Supercircuits microcameras, one an infrared monochrome camera and the other a high-resolution color camera. The video and audio signals are relayed by a X-10 2.4 GHz video transmitter-receiver pair.

EyeBot has made numerous appearances at The Robot Group events. The kids love EyeBot because it is approachable and appears to dance with them.

In addition, EyeBot appeared in the 2001 Robert Rodriguez film, Spy Kids.

Mark Pauline’s Survival Research Laboratories put on a show entitled “The Unexpected Destruction of Elaborately Engineered Artifacts : A misguided adventure in risk eradication, happening without known cause, in connection with events that are not necessarily related” at Longhorn Speedway, Austin, TX on 1997-03-28.

The SRL show was produced Bill Craig, Tom Davidson, and Paco X with substantial logistical assistance provided by Diana DeFrancesco.

For reasons of liability, The Robot Group, Inc. was not involved in any way with the production or the promotion of the show. Individual members were free to volunteer or help as they wished.

[Editorial note : I am awaiting Mark Pauline’s permission to use the Austin show’s poster as the featured image on this page.]

Eric Lundquist‘s Mobile Robotic Platform was an experimental built-from-scratch design with several unique features. Its behavior was very moth-like in that it chased the brightest light that it could detect. Obstacles were detected and avoided with feeler wires on 3 sides.

The brains of the Mobile Robotic Platform were a Parallax BASIC Stamp I providing 8 I/O lines and programming in a dialect of BASIC. Eric added a Stamp Extender that provided an additional 16 I/O lines.

The BASIC Stamp drove the motor and direction relays, the LEDs, and the Piezo buzzer. It also monitored the status of bumpers and polled light levels from its 3 photocell “eyes”.

The base was painted pine shelving material. Not only was this low cost, it did not require any specialized tools to work aside from a circular saw. It also made it exceptionally easy to mount, fasten, and rearrange things.

Eric’s ultimate goal with this project was to add several more BASIC Stamp controllers to make a distributed parallel architecture. This would have allowed more complex behavioral responses and interactions with the environment.

[Editor’s note : This information was extracted from an entry in an old version of The Robot Group web site archived by the Wayback Machine on 1996-12-04. Sorry, no photographs have emerged to-date.]

Negative Head is another face character for the planned robot theatre performance being directed by Brooks Coleman. The Negative Head is made from street lamp parts and servos. It creates face movements by overlaying transparent patterns to grids.

Leon Hubby proposed this project.

“Arthur … The Door Butler will resemble a very normal door. As you approach, you will see a door mounted in a partial wall with a very standard motion detector mounted at the top and a porch light to the side. A welcome mat will greet the visitors.”

“As the visitors approach, the motion detector will turn on the porch light and enable the door to greet the individuals. When the visitors step on the welcome mat, Arthur will open and then close the door for them. First, a compartment on the side of the door will open, a robotic arm will unfold, raise itself, and position to grasp the door knob. Arthur will then grab the door knob, rotate it, and open the door. A mat on the other side of the door will signal Arthur that the individual has passed through. The arm will then close the door, release its grip, and refold itself up closing its access door. “

“Art, as they say, is in the eye of the beholder. From my perspective the door represents a sculpture in motion. The image of an automatic door does not invoke much artistic impression. A door that lends a hand and opens itself, however, tends to be a bit more intriguing, if not novel. The technological content is centered around making a light-weight yet strong arm and gripper. This project will explore the use of different sensors to detect individuals, the door knob, etc. Differing techniques will be used to center the gripper on the door knob, close around the knob, and rotate to open it. This project will also explore the control aspects using the HC11E9. Special efforts and attention will be placed on the construction of the arm in order to build a light-weight, strong arm. The arm will be constructed of either PVC pipe or Styrofoam coated with epoxy fiberglass.”

RoboVision was a quick virtual reality (VR) project by Tom Davidson and Sonia Santana. The aim of the project was to provide attendees at RoboFest 7 a feel for what a robot’s vision might be like.

The project’s components were two VictorMaxx Stuntmaster VR headsets which had their video inputs wired to Supercircuits microcameras. The Stuntmaster had a single camera screen. The microvideo camera was mounted on the outside of the head gear with the battery power unit worn as a belt pack. An on/off timer switch was been wired to the helmet to allow more participants equal access. The entire head unit was covered with a cardboard mask design similar to that of the Megabot Army for a cool robot head appearance.

There was ample room in the head gear to allow for downward vision so that the person wearing the helmet could walk around and avoid tripping over stuff. The camera images that were projected into the headset screen were feeds from various mobile robots such as Commander Salamander and Mobile Platform and Dweebvision.

Editor’s note : The contents of this page were extracted an archived entry found on the Internet Archive’s Wayback Machine. The page, originally on Carlos Puchol’s web space at The University of Texas – Austin, was archived on 1996-12-31.

Introduction to the Mobile Platform

The mobile platform project is designed to provide ground-based mobility to experimental sensor and control systems, allowing them to traverse level surfaces such as building floors, and possibly streets and backyards. Think of it as a Hero robot on steroids.

Mobile Platform Mechanical System

The mobile platform is supported by two main drive wheels, with stability augmented by fore and aft caster wheels. Depending on distribution of weight in the platform and payload, it may be self-righting through balancing about the main wheel axis. Possible caster wheel heights are bounded on the low end by the need to negotiate unlevel surfaces and, on the high end, by the need to maintain the platform more or less level during dynamic maneuvers. Caster wheel mounting heights and possibilities for controllable height adjustments need to be investigated.

Mobile Platform Electrical / Electronic System

The mobile platform electronics are designed for control via a Motorola 68HC11 microcontroller Evaluation Board (EVB). The EVB receives movement commands from a higher authority and performs the necessary control functions to drive the platform motors. The EVB has been used as a basis because it is a handy development system. Eventually the motor drive circuit board will probably have an on-board HC11.

Control is currently passed to the EVB via a standard serial port for testing in conjunction with a data terminal. Eventually control will be migrated to the HC11 Serial Communications Interface (SCI) for interprocessor communication.

The motor drive power electronics reside on a circuit board with the same dimensions as the EVB and similarly placed 60-pin connector. It is capable of being mounted, with a suitable connector, as a daughter board on top of the EVB. Logic and motor drive circuitry are separate, with optical coupling of control and status signals in both directions. Motors are controlled via enable and direction signals. The enable is pulse width modulated (PWM) to control motor speed. In addition to the individual motor enables, a global driver enable allows shutdown of the entire power output stage. An overcurrent sense signal is sent back from the motor driver circuit to the HC11.

Each motor driver consists of four MOSFET transistors in an H-bridge configuration, controlled by a _____ IC. The most recent circuit version is equipped with IRF540 MOSFETS, giving it current capability of 27 A continuous, 108 A peak. This appears to be a reasonable transistor size for efficient operation at anticipated motor power levels. MOSFETS with higher current ratings may be substituted as required. The motor driver circuit is currently programmed for overcurrent limit of approximately 20 A, which may be modified by changing the current sense shunt.

Optical encoders on the motor output shafts are used to feed back motor position to the HC11. Each encoder consists of a pair of optical interrupters and an encoder wheel. The encoder sensors use a Schmitt trigger buffer to control encoder hysteresis. Optical encoder outputs are fed to the HC11 via connectors on the motor driver board. Connectors are 4-pin .100 type.

The motor driver circuit board is designed to operate with input voltage in the 5V-30V range. Full turn-on saturation of the MOSFETS is not guaranteed below 10V, so operation is not recommended in this range with a large motor load. Power connectors on the power board are Molex .093 series 2-pin connectors, connecting to male connectors on batteries and female connectors on motors. The motor drive circuit is fused with a standard automotive type fuse. The fuse should protect against melted wires and boiling batteries in the event of an output short. Current limiting by the transistor driver IC should protect the MOSFETs to some degree. This will no doubt be determined experimentally at some time.

There is an undesirable and potentially exciting design defect on the current version of the power board, resulting in runaway full-speed drive of the motors when power is removed from the control logic. This will be corrected on future versions. For the moment, it is necessary to ensure that logic power is applied prior to application of motor drive voltage, and motor drive voltage disconnected prior to disconnection of logic power.

Control Algorithm

General

The HC11 program which controls platform motion is mainly interrupt-driven. Encoder transitions are serviced as they occur. A real-time counter schedules updates of the trajectory generator and control loop. PWM transitions are controlled by HC11 internal timers, which are reset at the PWM frequency. Implementations of these functions are more or less similar to HC11 databook examples.

Movement Command Set

Platform movement is directed through commands to the HC11 via the serial port. The following is a summary of currently implemented commands :

“Magnitude”, a parameter in many commands above, is expressed in terms of encoder counts, and the relation to physical movement distance is a function of encoder resolution, gear ratio, and wheel size. Encoders should eventually be sized such that some whole number relation exists between counts and distance in standard units of measure. Radius is specified in increments of half the vehicle track.

Commands as currently implemented return prompt strings to the data terminal. Such information will be omitted for interprocessor control via the SPI.

Wheel Position Settings and Trajectory Generation

Each wheel has an associated destination position counter. The count values are modified through addition and subtraction of increments for instantaneous movements. Velocity commands cause the velocity value to be added to the wheel counts at the trajectory generation timestep interval. When a non-straight path is directed via the Radius command, the destination counts are incremented differently to achieve the desired radius. Operation at large radii is not smooth; the algorithm may be modified someday.

Translation, rotation, and velocity commands may be overlaid with predictable, though not always intuitive, results. In general, translation and rotation commands are intended to be applied disjointly, and separately from velocity commands. Velocity and radius commands are intended to be used together in a smooth manner. All commands take effect immediately but translations and rotations modify endpoint positions, whereas velocity and radius commands modify the incremental setting of new endpoints.

Eventual additions to the command set may include profiled moves, consisting of acceleration, maintained velocity, and deceleration. Other means of limiting acceleration and jerk forces via programmable limits are possible. Another feature, primarily applicable to translation and rotation commands, would be the ability to queue commands, i.e. move forward 5, turn left 2, move forward 8. Eventually the command set will probably need to be divided into two or more distinct modes of operation.

Encoder Sensing and Actual Position Determination

Optical encoders send two digital signals in quadrature to HC11 inputs. Transitions on one signal are recognized, at which point an interrupt routine reads the other signal and determines direction of encoder motion. New position is compared with previous position for the possibility of encoder error which is not really handled correctly right now anyway. Then the wheel position count is incremented or decremented as appropriate.

Generation of Motor Force Function

Voltage applied to each motor is determined via a comparison between destination position and actual position. If there is any difference, the control algorithm exerts force through the motor to drive the error to zero. The position control is implemented in a proportional-integral-derivative (PID) loop, with command-settable gain values for each term. The motor PWM duty cycle is also subject to a command-settable limit. The result of the control calculation is a duty cycle, which is used by the PWM logic to generate a PWM output from the HC11 for the motor driver circuit.

Error / Failure / Problem Resolution

Some work needs to be done in recognizing problems with platform motion such as bumping into objects, motor overcurrent, encoder / drivetrain / wheel slip, etc., and acting on these problems accordingly. The control algorithm will need to shut down activities which are causing problems and report back to its higher authority.

Balancing Act

Since the platform has two wheels, fairly responsive motors, and a dedicated controller, it may be possible to perform active balancing of top-heavy loads without relying on the caster wheels. This is actually not that farfetched, but would require some attitude-sensing hardware and algorithm development. It would also be totally cool.

RoboFest 7 was held September 14th and 15th, 1996 at Dobie Mall, Austin, Texas. Dobie Mall was one of the major sponsors of RoboFest 7 and we are grateful to them for their support.

The festival times were 10:00 a.m. to 6:00 p.m. on Saturday and noon to 5:00 p.m. on Sunday. Admission was $4.00 for adults and $2.00 for children under 12 years of age.

The Robot Film Festival, at Dobie Theatre, featured three films with robotic themes. Admission price for each film was $3.50. For more information and descriptions of the films browse the film festival web page.

An official press release was prepared along with lists of the exhibits, the exhibitors, the guest speakers, and the volunteers (without whom none of this would have been possible)

The following businesses were sponsors of RoboFest 7 :

Additional support and in-kind services were provided by :

The background material for this page is derived from archived pages (1, 2) on the Internet Archive Wayback Machine